More Schools Won’t Solve Nigeria’s Education Crisis

Nigeria has the largest number of out-of-school children in the world - Over 13 million children.

Unsurprisingly, poverty plays an important role. 72% of the poorest children are out of school, compared to 3% for the richest. Gender and region also play a part, with girls more likely than boys to be out-of-school. And children in the north—the most economically depressed region of the country and focal point of Boko Haram’s insurgency—are out-of-school at higher rates than their southern counterparts. For instance, 55% of school-aged children in Bauchi are out of school; in Anambra, that number is 6%.

The North East has a high % of out of school children

According to the Universal Basic Education Act of 2004, every Nigerian child is legally entitled to nine years of uninterrupted basic education, including primary schooling and three years of junior secondary school. These out-of-school numbers, however, represent a failure of policy to deliver this entitlement to all children.

An intuitive—and necessary—reaction to Nigeria’s out-of-school problem is to call for the government to invest more resources in the country’s education sector. Such investments might include building new schools or adding more seats to existing schools to increase enrollment. It might also mean additional financing for teacher training and making schools more accessible, such as feeding programs and provision of free uniforms and textbooks.

While those investments are critical, we must not neglect an important fact: that it is not enough to simply enrol children in school. Policies must go much further to ensure that children learn while they are in school.

There is abundant evidence showing that many Nigerian children do not learn much even when they are in school. The latest evidence comes from the recently launched World Bank Human Capital Index (HCI), which measures the amount of human capital that a child born today can expect to attain by age 18.

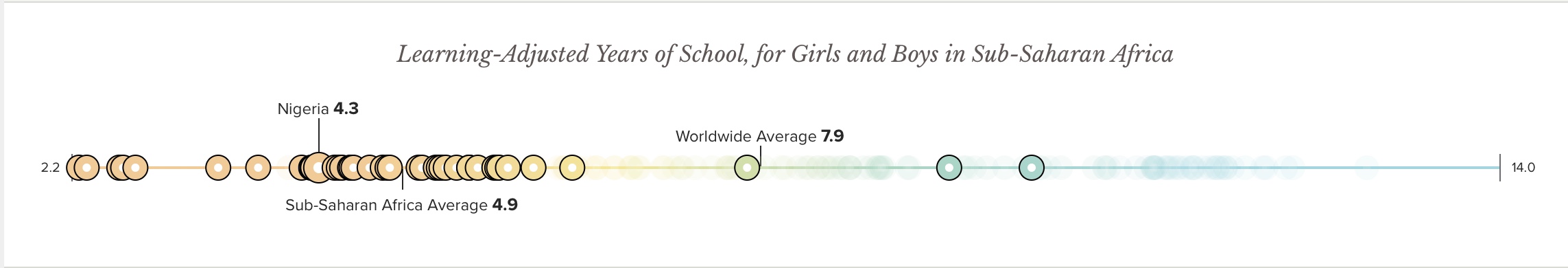

According to the Index, a child born in Nigeria today will acquire, on average, 8.2 years of school by the age of 18. However, when the years of school are adjusted by the quality of learning, we find that Nigerians are learning the equivalent of only 4.3 years of school.

Put in more practical terms, this implies that the average child who completes JSS 2 (second grade of Junior Secondary School) would have learned only what a primary 4 student is supposed to learn.

What’s more, the index shows that children in Nigerian schools lag behind other African children in terms of learning.

Worth noting is the fact that indices such as the HCI might even understate the problem since they only reflect the national picture and are constructed based on a sample of students who actually take standardized tests. When we look at children’s learning outcomes at the state level, we find that students’ learning—their acquisition of literacy and numeracy skills—might have declined in recent years. For instance, one assessment of students learning outcomes in government schools in Enugu, Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Kwara, and Lagos states shows that literacy and numeracy scores for grade 2 students have worsened since 2014. Poor performance on such assessments reveals the inability of students to complete basic cognitive tasks such as computing 2 + 3.

Nigeria lags African peers in education quality

Without a doubt, Nigeria has a learning crisis.

Several factors might explain these poor learning outcomes, such as the reality that many teachers do not show up to class, and, even when they do, their teaching is of low quality. Further fueling the lag in learning is the fact that poor children start school with severe nutritional and developmental disadvantages that undermine their preparedness to learn in class.

Beyond these factors though, the learning crisis itself plays a role in keeping children out of school in at least two ways. First, it limits students’ ability to progress within the education system. And secondly, it reduces incentives for parents to enrol and support their children in school. Low-quality learning translates to poor performance on important tests such as the primary and junior secondary school-leaving examinations. Consequently, many students are likely to drop out of the system after failing such exams. Further, research suggests that poor parents are less likely to make investments to keep their children in school if they perceive the quality of education to be low.

Despite its severity, Nigeria’s learning crisis does not receive the attention it merits. About 90% of the 2018 education budget is allocated for recurrent expenses, leaving too little room for investments in strategies that directly impact students’ experiences in the classroom.

There is still hope.

it is encouraging to note that the Universal Basic Education Road Map for the 2015 – 2020 strategy period lists as a policy goal the need to “ensure the acquisition of appropriate levels of literacy, numeracy, manipulative, communicative, and life skills needed for laying a solid foundation for life-long learning.” One implication of this policy goal is that policymakers urgently need to deliver stronger learning outcomes for every dollar that is spent on education. Where more clarity is required, though, is on the specific policies and programs that the government can adopt to reach the goal of putting students’ learning first.

One promising approach is the Teaching at the Right Level strategy whereby students are grouped into classes according to their learning level as opposed to their age or grade. Instead of focusing on following a rigid curriculum, this approach requires teachers to focus on meeting students’ learning needs by teaching at their current skill levels in math, reading, writing, and comprehension. In India, this approach has led to significant improvements in learning outcomes for children in government schools, and it might hold relevant policy lessons for Nigeria.

Regardless of Nigeria’s preferred policy approach, it is clear that building more schools or increasing the size of the education budget alone will not solve the crisis in the education sector. In our legitimate pursuit for more significant investment in education, we must not neglect the importance of learning. Ending the education crisis requires creative policies and programs that will simultaneously pursue the goals of increasing enrollment, limiting drop out rates, and—especially important—improving students’ learning outcomes.

In any part of the world, education is supposed to be the primary enabling tool for individuals to rise above poverty and overcome the circumstances of their birth. It ought to serve as the lubricant for upward economic mobility. For Nigerians, the learning crisis threatens to erase any hope of education serving as a way out of poverty.

Nigeria’s children deserve better. They deserve not only the chance to go to school but also the high-quality service delivery to ensure that they learn while in school.

Follow this Writer on Twitter @The_JamesLW .Subscribe to read more articles here.